Positive Psychology and Philanthropy: Reclaiming the Virtues of Classical Liberalism

—Robert F. Garnett, Jr.

In his Afterword to the 1993 edition of Reclaiming the American Dream: The Role of Private Individuals and Voluntary Associations (1993 [1965]), Richard Cornuelle laments that so few libertarians have embraced his vision of a flourishing voluntary community beyond the commercial sphere: “Most of my libertarian friends were willing to discuss possible market solutions to public problems, but, lacking any analytical device but market theory, continued to believe that anything that could not be done profitably should probably not be done at all” (186). Cornuelle’s remark points to an enduring gap in modern liberal thought. Most philosophical liberals celebrate philanthropy—“voluntary giving and association that serves to promote human flourishing” (Ealy, 2005, 2)—as a Tocquevillian alternative to the welfare state, yet their stock in trade conceptions of the free society tend to omit philanthropy, theorizing voluntary cooperation as an exclusively commercial affair.

Nowhere is this gap more evident than in the writings of F. A. Hayek. Hayek lauds voluntary associations for their uniquely effective “recognition of many [philanthropic] needs and discovery of many methods of meeting them which we could never have expected from the government” (1979, 50). He also praises Cornuelle’s Reclaiming the American Dream as an “unduly neglected book” which “seems to me to be one of the most promising developments of political ideas in recent years” (186 and 51). At the same time, Hayek develops his influential theory of the modern liberal order by way of a sustained critique of philanthropic action. Our desire to “do good to known people” is, he argues, an atavistic legacy of our tribal past and “irreconcilable with the open society” (1976, 168). Modernity has spawned a new moral code in which humane ends are better served by commerce than philanthropy, by “withholding from the known needy neighbors what they might require in order to serve the unknown needs of thousands of others” (1978, 268; 1979, 165; see also 1976, 90, 136, 144-45; 1978, 19, 59, 60, 65-66; 1979, 161-62, 168).

While leading scholars in the liberal tradition have begun to turn away from this narrow view of social cooperation in modern commercial societies (Murray 2006; McCloskey 2006; Gregg 2007), our mental maps still tell us that commerce and philanthropy are separate orders that don’t mix well. We continue, therefore, to wrestle with the question posed four decades ago by Cornuelle: How can we theorize a “free and humane” liberal order composed of market processes and “aggressive and imaginative voluntary action in the public interest” (Cornuelle, 1993 [1965], xxxiv ; 1992, 6)? Cornuelle’s goal was, and is, to forge a compelling theory of philanthropic action that would allow thinkers across the ideological spectrum to understand and embrace “the rationality and moral legitimacy of . . . [the] voluntary social process as completely as we now understand and embrace [the] market process” (1993 [1965], 198).

In this essay I seek to advance the Cornuellian project by placing it in dialogue with the emerging literature of positive psychology (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000; Seligman 2002; Haidt 2006; Keyes and Haidt 2003; Gable and Haidt 2005). The positive psychologists’ conceptions of human nature, freedom, and happiness strike a fresh synthesis of classical (especially Aristotelian) and modern views of the human. Their approach offers a valuable corrective to the Cold War liberalism of Hayek and others whose positions were crafted in strategic opposition to traditions they regarded as precursors to socialism, including much of Aristotle’s ethics, politics, and economics (Hayek 1967 [1947]; 1988). I employ the positive psychologists’ approach here as a means of enriching Cornuelle’s account of philanthropic action in Reclaiming and to envision new lines of classical liberal conversation regarding the nature and significance of philanthropy in contemporary commercial societies.

The Hayekian Impasse

A good starting point in seeking to understand Hayek’s exclusion of philanthropy from his vision of the Great Society is his 1947 address at the inaugural meeting of the Mont Pélèrin Society:

“The basic conviction which has guided me in my efforts [to bring this meeting about] is that if the ideals which I believe unite us, and for which, in spite of abuse of the word, there is still no better name than liberal, are to have any chance of revival, a great intellectual task is in the first instance required before we can successfully meet the errors which govern the world today. This task involves both purging traditional liberal theory of certain accidental accretions which have become attached to it in the course of time, and facing up to certain real problems which an oversimplified liberalism has shirked or which have become apparent only since it had become a somewhat stationary and rigid creed” (Hayek 1967 [1947]).

Aristotle’s ethics and theory of social order were among the chief targets of Hayek’s effort to “[purge] traditional liberal theory of certain accidental accretions which have become attached to it in the course of time.” Hayek saw modern socialism as a tragic misapplication of Aristotle’s concept of oikos —a face-to-face community in which order arises as “the result of deliberate organization of individual action by an ordering mind . . . and only in a place small enough for everyone to hear the herald’s cry, a place which could easily be surveyed” (1988, 11, 45-47). Through a series of essays beginning in the 1950s and culminating in The Fatal Conceit (1988), Hayek argued that the socialist ideal of an economy in which distributive justice and efficiency could be systematically engineered was based on an intellectual error: a failure to appreciate the profound difference between ancient and modern forms of economic order.

Carrying his argument one step further, Hayek classifies philanthropy as a species of Aristotelian socialism. Like socialism, philanthropy enjoins us “to restrict our actions to the deliberate pursuit of known and observable beneficial ends” (Hayek 1988, 80). From Hayek’s perspective, this diminishes, rather than enhances, each individual’s capacity to assist others. In a memorable turn of phrase, he claims that a social order in which “everyone treated his neighbor as himself would be one where comparatively few could be fruitful and multiply." Persons committed to finding “a proper cure for misfortunes about which we are understandably concerned” ( 13) should devote less attention to charity per se and more “towards earning a living,” because the latter will “confer benefits beyond the range of our concrete knowledge” (81) and provide “a greater benefit to the community than most direct ‘altruistic’ action” (19).

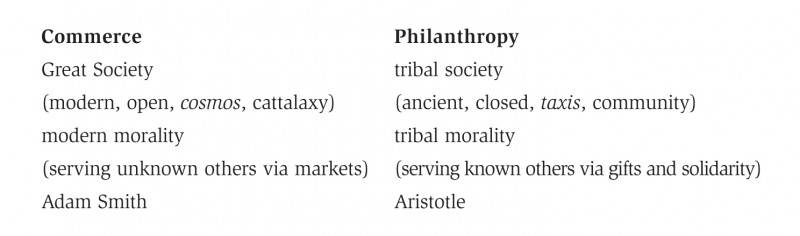

Hayek’s thinking about philanthropy is thus structured as a series of binary oppositions, roughly inverting the orthodox Marxist distinctions between socialism and capitalism (Hayek 1976; 1978; 1979; 1988):

While acknowledging that altruism and philanthropy “continue to retain some importance by assisting voluntary collaboration” and that this frequently requires us to “live in two sorts of worlds at once” (1988, 18), Hayek insists that these “old instinctual responses” play no necessary role in the modern liberal order. The ancient moral imperative for man to do “visible good to his known fellows (the ‘neighbor’ of the Bible)” is ultimately “irreconcilable with the open society to which today all inhabitants of the West owe the general level of their wealth” (1978, 268).

Interestingly, near the end of his brief discussion of Cornuelle and the independent sector in volume 3 of Law, Legislation, and Liberty (Hayek 1979), Hayek expresses a desire to explore more fully “the actual and potential achievements of the independent sector”: “I wish I could write about the subject at length, even if it were only to drive home the point that public spirit need not always mean demand for or support of government action. I must, however, not stray too far from the proper subject of this chapter, which is the service functions which government might usefully perform, not those which it need not take upon itself” ( 51).

Without overreading the passage, it seems clear that the philosophical and narrative structure of Hayek’s larger argument imposed constraints that prevented him from exploring this particular avenue of thought. Had he done so, Hayek might have been able to develop a different and arguably richer vision of civil and commercial society. Had he found a way to theorize the role of voluntary and philanthropic associations in a modern liberal order, he might, for example, have crafted a more philosophically consistent vision of how to enhance equality of opportunity (“the chances of anyone selected at random”) without disabling the market process (Hayek 1976, 132). Instead, Hayek’s dogged efforts to defend market processes against their socialist critics seem to have placed severe limits on his ability to integrate philanthropy into his baseline conception of the Great Society.

The Aristotelian Liberalism of Positive Psychology

Positive psychology emerged in the late 1990s as an internal critique of mainstream psychology, somewhat parallel to Cornuelle’s intervention into mainline libertarianism in the 1960s. Both laid claim to neglected regions of human action and benefaction by reasserting a “positive” view of human nature. Cornuelle’s faith in the energy and self-organizing potential of the independent sector was based on the assumption that human motivation includes an irreducible “hunger to help others” (1993 [1965], 62) “as powerful as the desire for profit or power” (61). For their part, the positive psychologists have endeavored to offset mainstream psychology’s “inappropriately negative view of human nature and the human condition” (Keyes and Haidt 2003, 3), particularly its “obsession with pathology” (Haidt 2006, 167). Seligman, Csikszentmihalyi, Haidt, and others aimed to shift the emphasis of psychology from “disease, weakness, and damage” to “the study of happiness, strength, and virtue” (Seligman 2003, xiv), “the conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing . . . of people, groups, and institutions” (Gable and Haidt 2005, 103). As Seligman explains: “The disease model does not move us closer to the prevention of [many] serious problems. Indeed, the major strides in prevention have resulted from a perspective focused on systematically building competency, not on correcting weakness. Positive psychologists have discovered that human strengths act as buffers against mental illness. . . . The focus of prevention . . . should be about taking strengths—hope, optimism, courage, interpersonal skill, capacity for insight, to name a few—and building on them to buffer against depression” (Seligman 2003, xv-xvi).

The positive psychologists situate their view of human nature within the Aristotelian branch of the liberal tradition. This in itself is an important complement to Cornuelle’s liberal philanthropy project because Cornuelle does not provide an explicit philosophical rationale for his brand of humanism. The positive psychologists’ commitment to an Aristotelian liberalism is reflected in their distinctive account of human happiness and its relationship to virtue. Happiness for positive psychologists refers not to joys or pleasures of the moment but to each individual’s “enduring level of happiness” (Seligman 2002, 45), a sense of well-being achieved through “good living.” This is Aristotle’s eudaimonia : happiness as “activity in accord with virtue” (Aristotle 1999, 163; see also 1-17, 116-17, and 162-66) that “cannot be derived from bodily pleasure, nor . . . chemically induced or attained by any shortcuts. It can only be had by activity consonant with noble purpose” (Seligman 2002, 112).

By making virtue a necessary condition for happiness, positive psychologists underscore the freedom and responsibility of each individual to discover and enact his or her own path(s) to greater happiness. Seligman, in fact, deems the role of voluntary action in the achievement and elevation of each individual’s happiness “the single most important issue in positive psychology” (2002, 45).

The positive psychologists also recognize the complexity and contingency of an individual’s pursuit of happiness. The fruits of good living always take time to emerge, and good living by itself is never a guarantee of happiness. (Aristotle emphasizes the latter point in his discussion of happiness and fortune in Book 1, Chapter 10, of Nicomachean Ethics .) Seligman explains it this way: The perennial question, “How can I be happy?” is not the right question, since “without the distinction between pleasure and gratification, it leads too easily to a total reliance on shortcuts, to a life of snatching up as many pleasures as possible,” which Seligman sees as a chief cause of depression (2002, 116). The right question is the one Aristotle posed 2,500 years ago: “What is the good life?” (120-121). Haidt observes, similarly, “Happiness is not something that you can find, acquire, or achieve directly” (2006, 238). Instead, the pursuit of happiness is an emergent process in which: “Some of the conditions [for happiness] are within you, such as coherence among the parts and levels of your personality. Other conditions require relationships to things beyond you. . . . It is worth striving to get the right relationships between yourself and others, between yourself and your work, and between yourself and something larger than yourself. If you get these relationships right, a sense of purpose and meaning will emerge” (238-239).

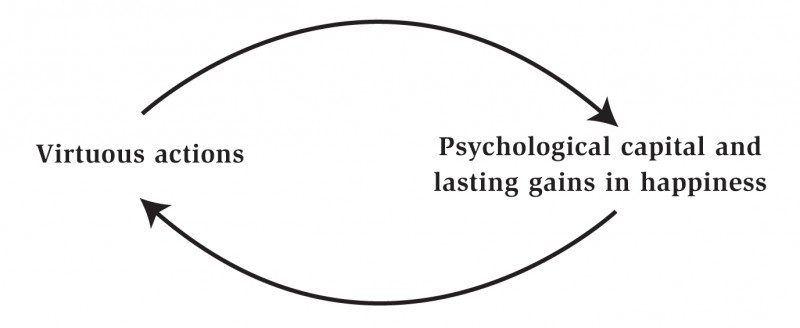

Another key contribution to the Cornuellian rethinking of philanthropy is the positive psychologists’ “virtuous cycle” model of personal growth and development. Building on the notion of happiness as an emergent effect of good living, this model depicts the pursuit of happiness as a long-term process of personal growth in which each person’s virtuous actions generate new psychological resources (knowledge, skills, character traits) which further expand his or her capacity and desire for future virtuous actions. This provides a rudimentary but fruitful starting point for thinking about the basic psychological, economic, and sociological elements of voluntary action and interaction beyond the commercial sphere. Schematically, we can envision it as follows:

Virtuous actions are variously defined by positive psychology literature as gratifications (Seligman 2002, 116), excellences (Haidt 2006, 170), or flow activities (Csikszentmihalyi 1990): activities that “engage you fully, draw on your strengths, and allow you to lose self-consciousness and immerse yourself in what you are doing” (Haidt 2006, 170). By linking virtue to each person’s unique strengths, the positive psychologists emphasize the subjective, discovery dimension of virtuous action. In Haidt’s translation of Aristotle, “a good life is one where you develop your strengths, realize your potential, and become what it is in your nature to become” (156-157). Virtuous action is also linked to happiness. Even if we do not experience them as pleasurable in the moment, virtuous actions may contribute to a lasting increase in our happiness if they immerse us “in a task that is challenging yet closely matched to [our] abilities” (95). We derive lasting happiness from such activities because they engage us at a deeply personal level, drawing upon and cultivating our unique strengths and interests. They generate positive feelings we can legitimately call our own because we have earned them. “It is not just positive feelings we want, we want to be entitled to our positive feelings” (Seligman 2002, 8, original emphasis).

Seligman uses the economic metaphor of capital to describe the future benefits we derive from virtuous action. Virtuous activities (as opposed to short-term pleasure-seeking) build our psychological reserves. They are “investments” that build “psychological capital for our future” (Seligman 2002, 116). This parallels Hayek’s broad economic definition of capital as “a stock of tools and knowledge . . . which we think will come in useful in the kind of world in which we live” (1976, 23). Like economic capital, psychological capital serves both as a buffer against adversity and as a means of producing or acquiring additional resources. One’s psychological capital would therefore include one’s accumulated stock of psychological strengths and capacities (“tools and knowledge”), including our hard-won knowledge of which activities constitute our “signature strengths” (Seligman 2002, 125-164)—in short, one’s capacity to pursue and attain happiness.

In good Aristotelian fashion, positive psychologists see happiness as being instrumentally valuable in addition to its intrinsic value. Happiness and psychological growth signal the achievement of good living and are valued ends in every human life. They also become or beget the tools, knowledge, and desire to engage in further virtuous actions. They enhance, in Seligman’s suggestive phrase, our “commerce with the world” (Seligman 2002, 43). Citing Barbara Frederickson’s path-breaking work, Seligman contends that psychological growth and its attendant positive emotions (“feelings of happiness”) make “our mental set . . . expansive, tolerant, and creative” and enable us to “build friendship, love, better physical health, and greater achievement” (35-36, 43). Psychological growth helps us to engage more effectively in commerce, broadly defined: the give and take of living and learning. Even in difficult times, our psychological capital provides the means to recognize and pursue new opportunities for win-win encounters, new opportunities to discover, exercise, and strengthen our capacities for virtuous (growth-generating) action. Positive psychologists therefore see each person as capable of achieving lasting increases in happiness through a self-sustaining process in which psychological growth is both a principal cause and consequence of virtuous action.

Implications for Philanthropy

The positive psychologists’ model of human action and well-being carries rich implications for philanthropic theory. Seligman invokes these connections frequently, to the point of defining positive psychology as an attempt to “[move] psychology from the egocentric to the philanthropic” (2003, xviii). He and his colleagues view philanthropy as a uniquely effective means of “commerce with the world” that not only causes but also is “caused by” happiness (2002, 43, 9; Haidt 2006, 97-98).

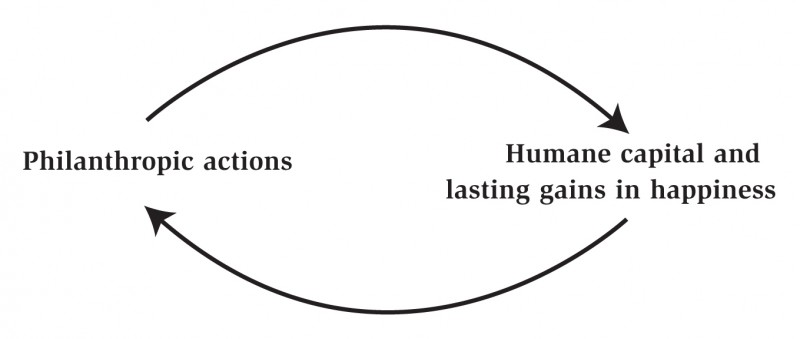

For my own purposes in this essay, I wish to explore briefly the contours of a specifically philanthropic analogue to the positive psychologists’ model of virtue-centered growth and discovery—a “virtuous cycle” in which philanthropic action fuels the extension and refinement of our humane capabilities, and vice versa:

This variation on the basic positive psychology model strikes me as a useful contribution to our understanding of the motives and mechanisms of voluntary action beyond the commercial sphere and thus as a potentially valuable underpinning for the Cornuellian vision of a liberal, post-Progressive philanthropy in which philanthropic action serves not just as a means of transferring resources but also as a locus of mutual uplift and social learning between donors and recipients (Cornuelle 1993 [1965], xxxiv; Ealy 2005).

Seligman and Haidt each describe the first phase, in which philanthropic actions generate new humane resources, via compelling examples of the ways in which philanthropic action creates uplift for donors. Seligman describes “the exercise of kindness” as “a gratification, in contrast to a pleasure,” since it “calls on your strengths to rise to an occasion and meet a challenge” (2002, 9). He and Haidt each cite experimental results showing measurable differences in the level and quality of happiness obtained from philanthropic actions versus activities that were considered “fun” (Seligman 2002, 9; Haidt 2006, 97-98, 173-174), lending empirical support to the Biblical adage that “it is more blessed to give than to receive.”

Philanthropic actions thus expand our individual capacity and desire for philanthropic giving. In addition to material resources, “humane capital” includes the individual’s unique strengths and virtues, the local and tacit knowledge of where and how these strengths and virtues might most effectively be exercised, and what Amy Kass calls (borrowing from the story of Prometheus) the philanthropos tropos : a disposition to promote the happiness and well-being of others (Kass 2005, 20).

Humane capital can also be generated by and for recipients of philanthropic giving. Kass reminds us of this neglected dimension of the philanthropic process by describing gifts as mutually beneficial interactions (2005, 21). For every giver, there must be a receiver; hence the receiver’s presence and receptivity are a form of gift to the donor. Today’s receivers are also tomorrow’s potential givers, enriched by the resources they have received and inspired by the gratitude they feel in response to these gift(s), and guided by the philanthropic know-how they gained in the process. More generally, gratitude and other positive emotions make one more aware of one’s capacities and desires to give. This is a key element in Richard Gunderman’s expansive vision of liberal philanthropy as the cultivation of each person’s “entrepreneurial” awareness of his or her unique capacity for giving: “The aim of philanthropic activity should be to transform people in need into people who believe they have something important to share, and who want to share it” (7).

In the second phase of the philanthropic virtuous cycle, higher levels of humane capital and happiness among donors and recipients create greater potential for sustained giving and civic engagement (Gable and Haidt 2005). This phenomenon is well documented in the positive psychology literature. Seligman reports, for example: “In the laboratory, children and adults who are happy display more empathy and are willing to donate more money to others in need. When we are happy, we are less self-focused, we like others more, and we want to share our good fortune even with strangers. When we are down, though, we become distrustful, turn inward, and focus defensively on our own needs” (2002, 43; Haidt 2006, 173-74).

In addition to this “happiness effect,” the growth of one’s humane capital also conveys (indeed, consists of) more skills and know-how for achieving mutual uplift by aligning one’s philanthropic actions with the needs and actions of others.

This simple model helps us to conceptualize philanthropy as a process of discovery, learning, and social cooperation in which our pursuit of happiness (not pleasure but Aristotelian/liberal flourishing) leads us to continually adjust our actions in response to feedback—to (re)invest our philanthropic resources in ways that are more rewarding to us and to the known and unknown neighbors who benefit from our actions. Put differently, it helps us to see philanthropy as a generative process of human betterment, creating positive-sum interactions among donors and recipients rather than one-way, zero-sum transfers. It thereby affirms and extends Gunderman’s vision of liberal philanthropy: “When we see philanthropy as part of a fixed-sum system, we perceive its mission in terms of redistribution. . . . [In contrast,] the most enlightened philanthropy aims at increasing non-fixed-sum relationships throughout a community. In other words, decreasing want is ultimately less important than increasing generativity, our capacity to contribute to our own flourishing. In this vision, philanthropy . . . enhances both our capacity and our inclination to make a positive difference in the lives of others” (2007, 41-42).

Beyond the Hayekian Impasse

Like Hayek in 1947, classical liberals in our post-Cold War era face a “great intellectual task,” of “purging traditional liberal theory of certain accidental accretions which have become attached to it in the course of time, and [to face] up to certain real problems which an oversimplified liberalism has shirked or which have become apparent only since it had become a somewhat stationary and rigid creed” (Hayek 1967 [1947]).

One area in which received liberal thought stands in need of substantial revision is the role of philanthropy in modern commercial societies. Growing numbers of liberal scholars are pushing forward on this front, seeking—with Cornuelle—to preserve the central lessons of the Hayek/Mises critique of central planning while reclaiming the humanitarian potential of commercial society by theorizing philanthropy as a form of social cooperation distinct from, yet complementary to, the commercial order. A necessary first step in this rethinking process is to move beyond the “oversimplified liberalism” of Hayek’s commerce-only view of voluntary social cooperation and his denigration of philanthropic motives as a nostalgic survival of pre-modern (and proto-socialist) cultural and intellectual mores.

Positive psychology adds a valuable voice to contemporary conversations about freedom and human flourishing by reasserting an Aristotelian view of the human condition and an Aristotelian liberal psychology geared to “promoting the best in people” rather than “preventing the worst from happening” (Keyes and Haidt 2003, 5). The positive psychologists’ work enriches classical liberal discussions of freedom in particular by articulating the value of both the negative freedom from coercion and the effective or “positive” capacity to pursue the good life as one defines it, including the freedom “to experience meaningful personal engagement in community life” (Ealy 2005, 4). From this perspective, philanthropic action serves to cultivate and extend our positive freedom to serve others, to develop and exercise our humane capabilities of “loving, befriending, helping, sharing, and otherwise intertwining our lives with others” (Haidt 2006, 134). In modest but significant ways, it helps us to imagine how to multiply the number of “personal outlets for the service motive” so that our humane desires and resources might be more effectively harnessed to address “complex modern problems” (Cornuelle 1993 [1965], 62).

The potential gains from this intellectual exchange are by no means one-sided. Positive psychologists can profit from the ideas and legacy of Cornuelle and those of leading-edge Hayekian scholars who have begun to explore the role of social capital in local and extended orders of human cooperation.

Positive psychologists seeking to better understand and support “positive institutions” could also benefit greatly from the large body of Hayekian and classical liberal thinking on the dialectical interplay between social institutions (formal and informal) and emergent processes of social cooperation. The writings of Hayek and other liberal economic thinkers could help to inform the positive psychologists’ accounts of the epistemological open-endedness of each individual’s pursuit of happiness exemplified in Seligman’s claim that “Building strength and virtue is not about learning, training, or conditioning but about discovery, creation, and ownership” (2002, 136), suggesting that individual strengths and virtues are not “given” but discovered via a process of moral entrepreneurship. The Austrian/Hayekian theory of individual action and the market process could also go a long way toward sharpening the incipient logic of the positive psychologists’ vision of the “pursuit of happiness,” in which individuals engage in ongoing processes of specialization and discovery, seeking to identify and hone their signature strengths, which in turn influence their capacity not only for philanthropy but also for economic trade and capital accumulation.

A further area in which mutual learning opportunities appear to be especially fruitful is the burgeoning literature on emergent cooperation within decentralized, nonmarket networks in which a new generation of Austrian economists is exploring, from a Hayekian perspective, the nature and importance of social capital as a means of generating the personal and interpersonal resources to sustain local and extended networks of voluntary cooperation outside the commercial order (Chamlee-Wright 2004, 2006, 2008; Chamlee-Wright and Lewis 2008; Chamlee-Wright and Myers 2008). These Austrian social capital theorists share the positive psychologists’ vision of individuals as socially embedded beings whose character and capacities are shaped by the social networks in which they live. Yet they have gone much further in their efforts to define and analyze social capital, in contrast to the positive psychologists, who have only begun to articulate their notion of “psychological capital” vis-à-vis the larger process of individual action, learning, and mutual adjustment they call the “pursuit of happiness.” This new Austrian work could help to clarify the overlaps and interplay between the psychological capital we possess individually and the social capital that resides in the intersubjective spaces of “informal (non-contractual) networks of [personal] relations, and the beliefs and norms which arise from and govern these structures” (Chamlee-Wright and Lewis 2008, emphasis added). In turn, the Austrian social capital project could itself be enriched by the positive psychologists’ focus on the cultivation and consequences of virtuous and philanthropic action.

Further conversation among positive psychologists and students of liberal philanthropy would help all of us tackle the Aristotelian, liberal task of theorizing a “free society” that leads to and depends on “flourishing human lives of virtue” (McCloskey 2006a, 497).

REFERENCES

Aristotle. 1999. The Nicomachean Ethics . Second edition. Terence Irwin, trans. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Chamlee-Wright, Emily. 2004. “Local Knowledge and the Philanthropic Process: Comment on Boettke and Prychitko,” Conversations on Philanthropy I : 45-51. ©2004 DonorsTrust.

―――. 2006. “After the Storm: Social Capital Regrouping in the Wake of Hurricane Katrina,” Southern Economic Association Meetings, Charleston, SC, November.

―――. 2008. “The Structure of Social Capital: An Austrian Perspective on Its Nature and Development,” Review of Political Economy 20 (January): 41-58.

Chamlee-Wright, Emily and Paul Lewis. 2008. “Social Embeddedness, Social Capital, and the Market Process: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Austrian Economics, Economic Sociology, and Social Capital,” Review of Austrian Economics 21 (Spring): 107-118.

Chamlee-Wright, Emily and Justus A. Myers. 2008. “Discovery and Social Learning in Non-Priced Environments: An Austrian View of Social Network Theory.” Review of Austrian Economics , 21 (2-3): 151-66.

Cornuelle, Richard C. 1992. “The Power and Poverty of Libertarian Thought.” Critical Review 6 (1): 1-10.

―――. 1993 [1965]. Reclaiming the American Dream: The Role of Private Individuals and Voluntary Associations. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Ealy, Lenore T. 2005. “The Philanthropic Enterprise: Reassessing the Means and Ends of Philanthropy,” Economic Affairs 25 (2): 2-4.

Gable, Shelly L. and Jonathan Haidt. 2005. “What (and Why) Is Positive Psychology?” Review of General Psychology 9 (2): 103-10.

Gregg, Samuel. 2007. The Commercial Society: Foundations and Challenges in a Global Age. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Gunderman, Richard B. 2005. “Giving and Human Excellence: The Paradigm of Liberal Philanthropy,” Conversations on Philanthropy II: 1-10. ©2005 DonorsTrust.

―――. 2007. “Imagining Philanthropy,” Conversations on Philanthropy IV: 36- 46. ©2007 DonorsTrust.

Haidt, Jonathan. 2006. The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. New York: Basic Books.

Hayek, Friedrich A. 1967 [1947]. “Opening Address to a Conference at Mont Pélèrin.” In F. A. Hayek, Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics , 148-59. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

―――. 1976. Law, Legislation, and Liberty , Volume II: The Mirage of Social Justice . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

―――. 1978. New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

―――. 1979. Law, Legislation, and Liberty , Volume III: The Political Order of a Free People . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

―――. 1988. The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. W. W. Bartley III, ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kass, Amy A. 2005. “Comment on Gunderman,” Conversations on Philanthropy II: 19-24. ©2005 DonorsTrust.

Keyes, Corey L. M. and Jonathan Haidt, eds. 2003. Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

McCloskey, Deirdre N. 2006. The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Murray, Charles. 2006. In Our Hands: A Plan to Replace the Welfare State. Washington, DC: The AEI Press.

Seligman, Martin E. P. 2002. Authentic Happiness. New York: Free Press.

―――. 2003. “Foreword: The Past and Future of Positive Psychology.” In Corey L. M. Keyes and Jonathan Haidt, eds. Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well- Lived, xi-xx. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Seligman, Martin E. P. and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. 2000. “Positive Psychology: An Introduction.” American Psychologist, 55 (1): 5-14.